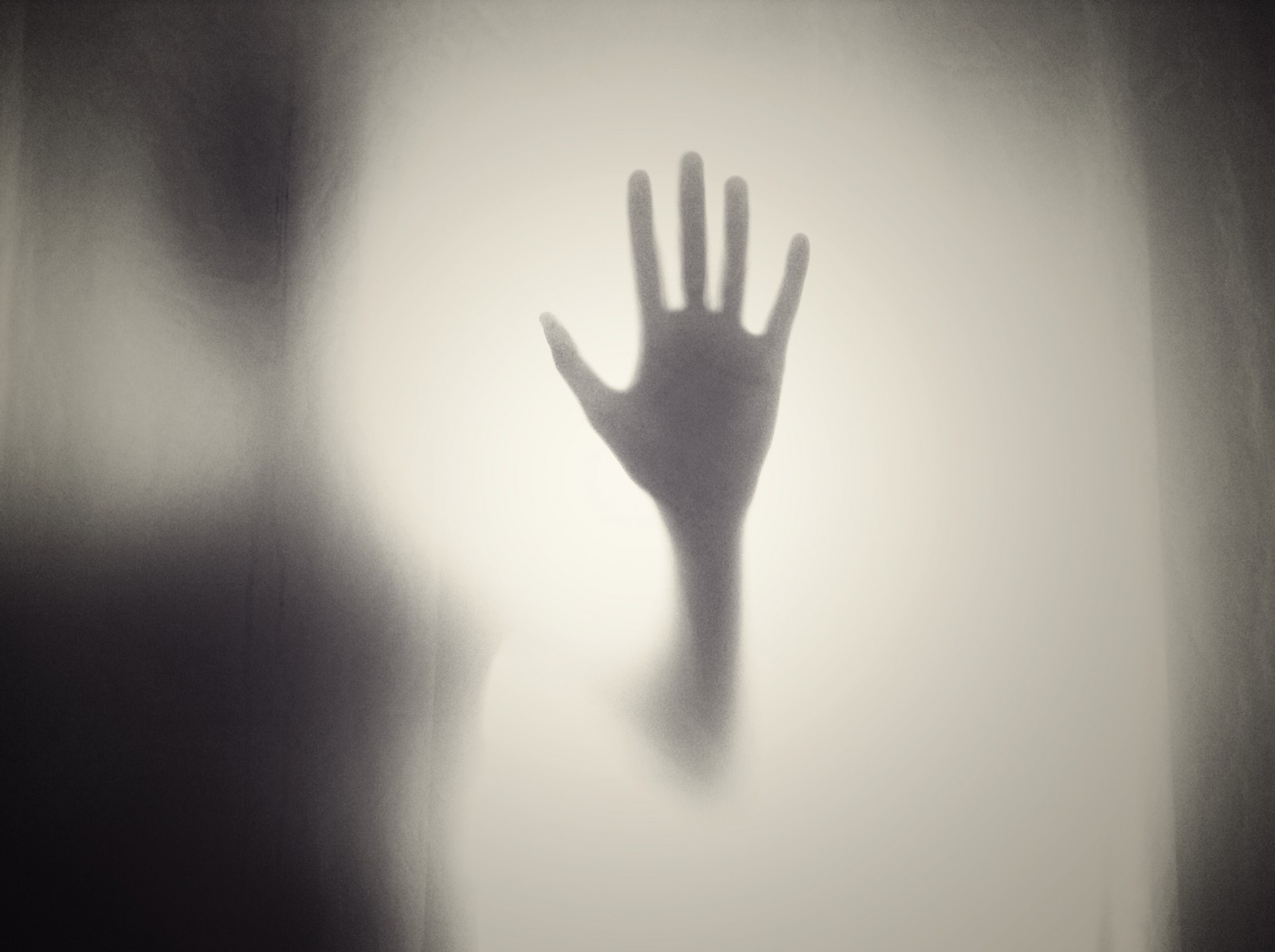

It started with an innocent enough question.

“Daddy, what are those white lines on your arm?”

“Those are scars.”

“How did you get them?”

“I cut myself.”

“How did that happen?”

“I did it on purpose.”

“Why?”

“When I was younger, I used to cut myself when I was angry or sad.”

I am not ashamed of my self-harm scars. They’re just a part of me, like my brown eyes, my depression, and my sense of humor. I knew that Namine would one day notice them and ask about them. I just didn’t think that day would come so soon. (Although now that I think of it, “soon” is all relative. Namine is almost nine years old!)

Namine and I talked about sadness and depression. We talked about the talking: about having someone you can trust. It’s not the first time that we’ve discussed her being able to talk to us about anything without fear of getting in trouble, and I’m sure, as she gets older, that it won’t be the last. It bears repeating.

Namine has a self-love that I’ve never felt for myself, and for that I’m thankful. She’s never shown signs of clinical depression. But since it can be hereditary, she may someday. Forewarned is forearmed, as the saying goes, and though you can never truly be prepared for depression, talking about it is a good first step.

Namine knows about death, having come so close to it personally. Not only she herself, but she’s lost a grandmother and a great-grandmother, and she was extremely close to both. She knows about suicide; the topic was touched on in one of her school books last year, actually. (Had I known ahead of time, I’m not sure I would have let her read it. But she did read it, and so we discussed it.) She knows that people hurt themselves on purpose, sometimes badly, when they’re not thinking straight. She also knows that I get sad sometimes, without cause or reason. (“Sad” being her word, and although it isn’t quite right, it’s close enough for her vocabulary and our discussion.)

It’s all we can do sometimes to surround ourselves with people who love us. Jessica was with me on the night I cut my arm, and without her present, I may have bled to death. I believe in honesty with my daughter, but on a level appropriate for her age. I won’t tell her now that I almost died, but as she gets older, she may learn it; I don’t have a problem with that.

For now, it suffices for her to know that her mommy took care of me. I count myself beyond blessed to have a wife who loves me, despite my depression. And that’s the point I wanted to get across: I am not in this fight alone; I have someone on whom I can depend. I want Namine to have the same trust in us, as her parents; the same assurance that she can depend on us.

So the most I can say about depression to my daughter — and to you, dear reader — is that communication is probably the most important thing you can have. Be there for the people you love. Be willing to talk. More importantly, be willing to listen. Just be there.

Leave a Reply